Perceived Age

"To live is to be other. It's not even possible to feel, if one feels today what he felt yesterday. To feel today what one felt yesterday is not to feel—it's to remember today what was felt yesterday, to be today’s living corpse of what yesterday was lived and lost." -- Fernando Pessoa

At 2:15 PM on June 5th, kids burst through school doors, sprinting towards three months of freedom. Summer felt endless back then, August an eternity away. A day at Great America stretched like a week, and road trips to LA lasted forever. Fast forward to 16, responsibilities piling up. Even then, going from freshman to sophomore year felt like 4 years. Now at 22, the passage of time feels significantly faster, with the years seeming to fly by more rapidly as the novelty of each experience diminishes.

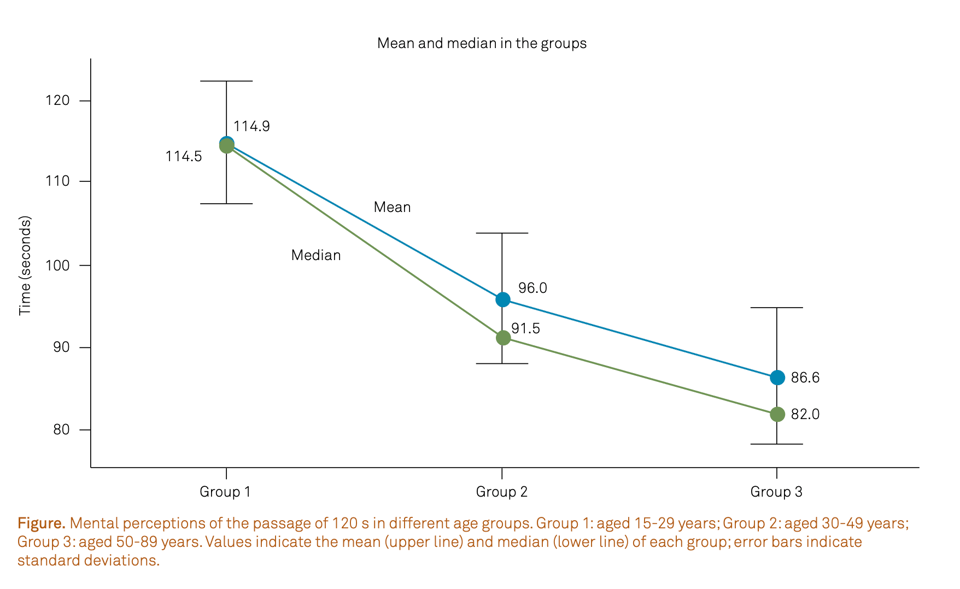

A study asked different age groups to mentally count 120 seconds. People under 30 averaged 115 seconds; those over 50 just 87. That's a 24% reduction in perceived time. This shift in perception isn't just random; it's rooted in the complex interplay of our brain's neurotransmitters, primarily dopamine.

[1]

[1]

Dopamine plays a significant role in how we perceive time. As we age, changes in dopamine function affect our internal clocks. When we're young, everything is new and exciting—first kiss, first job, first time living away from home. These novel experiences flood our brains with dopamine, making time feel elongated. As we age, novelty diminishes, dopamine decreases, and time seems to speed up.

Our internal clock system, predominantly dopaminergic, and our memory, which relies on acetylcholine neurotransmission, work together to shape our perception of time. A 2004 study showed that rats can estimate time intervals up to 40 seconds even without their cerebral cortex, indicating that time estimation is a subcortical process rather than a receptor like smell and touch. In humans, stimulants that boost dopamine function speed up the perception of time, while antipsychotic drugs or feelings of sadness and depression, which block dopamine receptors, have the opposite effect. On the other hand, novelty-induced time elongates our perception of time, while mundane repetition, like a dull office job, traps us in the illusion that time is shrinking.

Claudia Hammond, a psychology writer, introduces the concept of a "reminiscence bump," which occurs when we encounter novelty in the world of firsts (travel, relationships, etc.). This novelty is tied to how we form our identity, causing the brain to grasp onto details that solidify how we present ourselves to both ourselves and others.

"And at the place where time stands still, one sees lovers kissing in the shadows of buildings, in a frozen embrace that will never let go. The loved one will never take his arms from where they are now, will never give back the bracelet of memories, will never journey afar from his lover, will never place himself in danger of self-sacrifice, will never fail to show his love, will never become jealous, will never fall in love with someone else, will never lose the passion of this instant in time." -- Alan Lightman

The perceived acceleration of time as we age is a major cognitive illusion. Childhood memories seem endless because they were filled with constant discovery and the impairment of registering regret or anxiety about the past and future. Adulthood doesn't hold the same level of novelty. Repeated stimuli appear briefer than new stimuli of equal duration. Learning new things and taking on challenging cognitive tasks can potentially slow our internal sense of time.

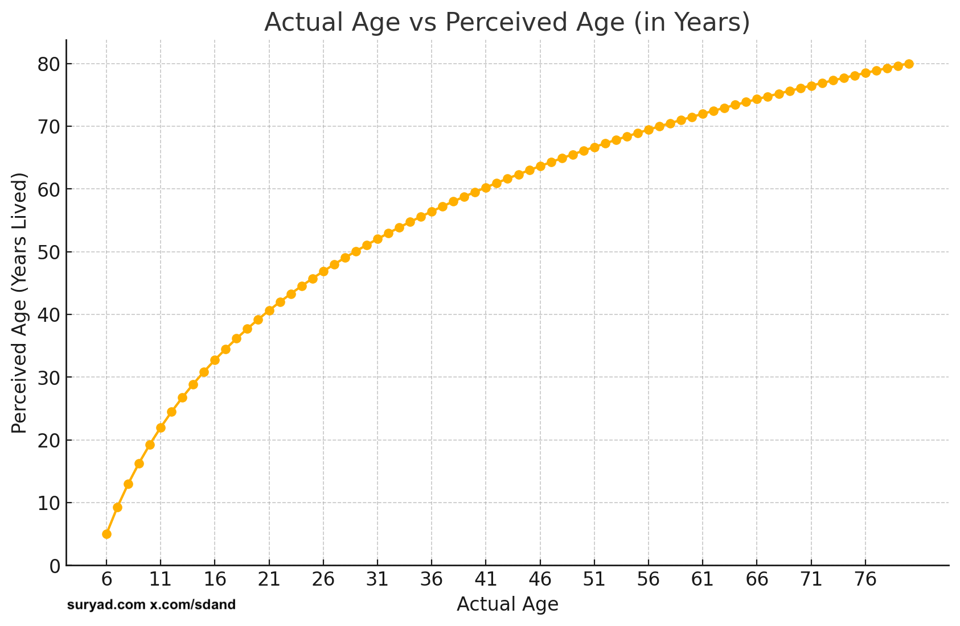

To further illustrate this, consider our conscious perceived age relative to our actual age. Discounting the first 5 years of life to childhood amnesia, when you’re 6, a year represents 16.67% of your life, by 13 it's 7.7%, and by 18 it's just 5.6%. “Perceived age” quantifies this, scaling our age to reflect our subjective experience of time passing. In other words at age 6 you’ve perceived 5 years of life but by 13 it feels like 26, each year feeling less significant than the last.

Time is a construct shaped by our neurobiology, psychology, and the dance of our daily lives. Our perception of time isn't fixed; it's malleable, influenced by dopamine levels, novel experiences, and cognitive demands. Understanding this can be empowering rather than daunting. While we can't physically stop time, we can influence our perception of it.

By seeking novelty, embracing change, and expanding our horizons, we can stretch our subjective sense of time. Trying new fruits, exploring different sports, subscribing to new forms of thought and radically new lifestyles(the amish and uncontacted tribes live tangentially different lives than we do for better or worse) add layers of childlike richness to life beyond the routines capitalism often dictates (buying new cars, food, consuming stuff generally).

Alejandro Jodorowsky's The Holy Mountain (1973), where surreal symbolism and rituals converge on a quest for spiritual enlightenment.

Realizing that your perceived age accelerates faster than your chronological age can make life feel like a blessing. You just need to set your life up once—start running, go to the gym, eat cleaner—and these habits will continue paying off throughout your life.

Whether it's due to fear, comfort, stability, reliance, or a plethora of other excuses, maintaining a dynamic and charged life correlates with your perception of time. Establishing better habits increases your chronological time, but by age 40, when every year begins to feel indistinguishable from the last, what do you have to lose by doing shit you have never done before?

It’s kind of over for you if you want to make it over for you before you even had the chance to make it. Having a career is another made up thing, it’s not real. Money is real but is infinitely more important earlier in life rather than later unless you’re pro-natalist insistent on leaving an inheritance; otherwise, it’s likely more useful at 20 than at 50. You have a good 80 years, why waste it doing one thing when you can cumulatively do a dozen things that touch a dozen different lives and communities?

“You waste years by not being able to waste hours.” —Amos Tversky

I didn't know it at the time, but June 5th was the last time I'd be at school for a full year. covid came and went, school felt more of a chore juggling it between projects (& my first and last fulltime job), but despite the madness I came out winning; it's hard to find who didn't somehow in the zirp era. I agree the first week of freshman year is the most important at any school, and the rest of the 4 years is marginally not. That was taken away from me, and I felt repulsed being (for a semester or so) surrounded by people who felt incessantly opportunistic that someone (job recruiter, VC, etc.) would give them a handout. Instead, here I am writing this blog post 4 years later.

If you’re reading this I probably am doing something right, or at least that's what I make myself believe. Probably driven by my paranoia and the fresh liquidity of 22 year olds on the market, I sense time is ticking even quicker, but life is a series of processes and systems glued by discipline and determination -- it's refreshing to be in the moment, with unlimited free will, embracing change, optimistic in a world where GDP goes up only, to be around working with people with unbridled ambition, and with time so endless it feels like June 5th again.

Thanks to Alex Reibman, Ankit Gupta, Anish Agnihotri, Caleb Sirak, Dar Sleeper, Jesse Michael Han, Justin Zheng, Khushi Suri, @mempooled, @spikedoanz for helping review and edit!

And thanks to Parth Chopra for inspiring the perceived age graph calculation [2].